During the weeks of the pandemic, I ran into an interesting artbook that approached visual culture, the theme of apocalypse, abandonment and ruins in an interesting way. The additional appeal was that is concentrated on video games. Due to its approachable style, the visual allure that imposed upon the reader not only the act of reading but as well looking and seeing, I was inspired to approach the author and talk in more detail about her latest project. The author in question is Joanna Zylinska – a writer, lecturer, artist and curator, working in the areas of new technologies and new media, ethics, photography and art. She is a Professor of New Media and Communications, and Co-Head of the Department of Media and Communications, at Goldsmiths, University of London. As the author of the aforementioned book, titled Perception at the End of the World (or How Not to Play Video Games), Joanna shared her experience in video games, motives to write about it and in-game photography and to be another interesting example of entanglement of gaming culture and academia.

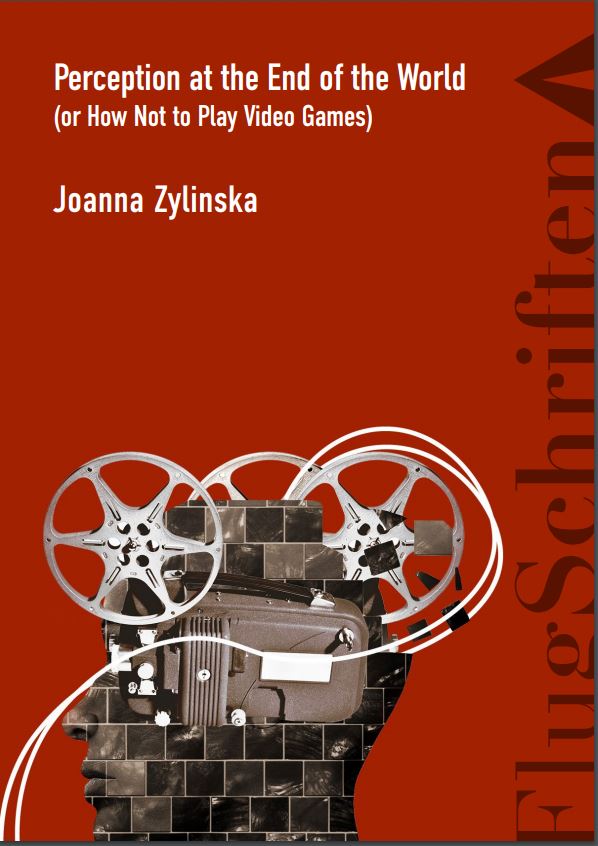

Hi Joanna, thank you for talking with us about your new book. Perception at the End of the World (or How Not to Play Video Games) raises many interesting points, on a textual as well as visual level. However, can you introduce our readers to this book on your own? What exactly is it about? The publisher of your book, Flugschriften, states that it “publishes short, sharp shocks to the system–whether this is the political system, literary system, academic system, or human nervous system’’. It is hard not to agree with that. What was your primary “system’’ to “shock’’ while writing this?

Thank you for your invitation and your interest in my work. Perception at the End of the World (or How Not to Play Video Games can perhaps be seen as a visual, textual and conceptual experiment. It’s an art book, featuring an essay by myself which explores how we see the world, but it’s also been designed as an object that explores the limits of our seeing. Video game environments have served for me as a laboratory in which I could explore and test those limits. The assemblage consisting of the gamer’s body, together with the controller, the screen and the avatar, create an interesting context for studying perception. In the process of playing a game, “seeing” reveals itself to be a bodily act, involving much more than just our eyes and our brain. This applies to real-life situations too, but the gaming experience both visualises and enacts this message about how we see the world by doing things in the world – and by becoming part of it. In this sense, the book is aimed to offer a shock to the human nervous system, by rethinking perception as environmental, as connected to the world out there, be it outside our window or on a computer screen. But it also aims to shock the literary system by being both a text to read and an object to look at. Finally, by considering some wider cultural implications of the aesthetics of some video games, especially those associated with the apocalypse, it also aims to challenge our current political and economic system. So there will be lots of shocks for the reader – but they shouldn’t be too painful, hopefully!

How did you decide to work with video games, especially with The Last of Us and Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture as your “case studies’’?

I work in a broader area of media theory and media practice. This is to say, I write about media – about processes of communication, about technological infrastructures of various media, about our increasing involvement with machines and data. I also make image-based works, remaining in conversation with the tradition of photography while exploring the photographic medium’s evolution in digital culture. But, disappointingly, one area of media I had very little to say about until recently was video games. As I reveal in the book, I was not a gamer before I started on the project. However, having visited the fascinating exhibition called Videogames: Design/Play/Disrupt at the V&A Museum in London in 2018, which explored the design and culture of contemporary videogames, I was struck by the amazingly rich visuality of video games, by their beautiful textures, and by the multiple universes created in game environments. This initial attraction was then fuelled further by a workshop on in-game photography I attended at the Photographers’ Gallery in London, at which I was introduced to the photographic practice within video games, using GTA V. After all this I decided I needed to give games a try. The reason I turned to The Last of Us and Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture as my first ventures into video gaming was because I was intrigued by their end-of-the-world theme. And I was keen to see how this theme would be realised visually. To a large extent both games delivered on that sense of excitement and anticipation I initially felt. Indeed, I drew a lot of pleasure from exploring different nooks of those two games, from lingering in their secret corners, from testing their edges. So the title of my book, Perception at the End of the World, refers to both the apocalyptic themes and to the actual edges of game environments, many of them not really designed for gaming yet offering something fascinating for artists and photographers like myself. My photographic project Flowcuts included in the book is an outcome of this visual exploration.

In the book you mentioned “ruin porn’’, a fascination with watching, experiencing and depicting post-apocalyptic surroundings and ruins. What do you think, where does this fascination come from? In other words, why are apocalyptic and postapocalyptic themes so popular with people, whether they are gamers, artists, or something else?

With the term “ruin porn” I am referring to the recent proliferation, in different media, of the practices of imagining and imaging a certain future “after the human” and after the end of our human world. Such images of the vanishing of the world, coupled with viewers’ fascination with images of decay which show the world as it soon will be, have some clear historical antecedents. These stretch from the sublime Romantic landscapes of ruined abbeys by the likes of Giovanni Battista Piranesi and Hubert Robert, all the way through to paintings such as Joseph Gandy’s Rotunda, commissioned by John Soane, the architect of the Bank of England, and depicting that bank as a ruin even before it was built. This visual practice of “ruin porn” has gained a new inflection in a period in which issues of the 2008 global economic crisis and the impending climate catastrophe have come to be experienced and articulated with an ever increasing intensity: we can think here of the seductive and haunting images of Detroit, a financially bankrupt North American city with a glorious industrial and architectural past, which widely proliferate on the Internet. Popular culture, especially mainstream film and TV, have of course been at the forefront of turning catastrophe into a visual entertainment/relief trope for many decades: we can mention here classic movies such as The Day the World Ended (1955), Armageddon (1998) and Children of Men (2006), as well as TV series such as ABC’s Invasion (2005-2006). But, arguably, something has changed of late: a new sense of total disaster and total obliteration, without any notion of heroism or hope, has been ushered in by more recent productions such as the History Channel’s Life after People, HBO’s The Leftovers or Netflix’ Into the Night, as well as the video games we have been discussing, such as The Last of Us. Last but not least, the current context of the Covid-19 global pandemic creates both a new need and a new actualisation of the fears and desires expressed by apocalyptic themes. Seeing the end of the world on the screen becomes a way of containing the danger and the associated anxiety, framing it as a picture to be seen – but also to be put away when we want to. We also have to remember that the apocalypse is not just about a disaster: there is salvation and redemption at the end of the suffering in most apocalyptic narratives across history.

Besides obvious distinctions, how different is the experience for you as a photographer of shooting (i.e. photographing) within a video game environment? How popular is this “new para-photographic genre’’, as you call in-game photography?

Gamers have been taking screenshot images of their achievements and saving interesting-looking locations discovered on their game quests for a long time. Eventually game developers recognised a PR opportunity in this spontaneous practice and introduced a dedicated camera mode to their games. We can mention here a simple camera device held by a character, such as a reporter in Beyond Good and Evil, a sophisticated camera function transforming the whole screen into a camera while mimicking the exposure and processing of a real-life optical device in The Last of Us, or even an option for augmented-reality capture in Pokémon Go. Alongside these playful “side” practices, so to speak, over the recent years many artists (like myself) have flocked to game environments to do other things in games, rather than just pure gaming. Games started to be seen as fertile environments for exploration and creative image-making.

I presume that you leave the interpretation of your work to the reader, however, I would like to hear from you about how you got to the idea for this visual style of your book. Some parts are highlighted, some are in a different color, there is this one great page (page 30) completely standing out as a copy, or a scan (?). What message do you want to convey to the reader who is not maybe so well-versed in theory but is interested in photography, especially in the context of video games?

I was very lucky to have worked with an amazing designer, Felipe Mancheno, on this book. Unlike myself, Felipe was an experienced gamer, and he was also familiar with many of the ideas about media I was writing about. So that helped a lot with our discussions about how the book should look. I originally asked for my Flowcuts photographs (which are in fact composites taken from various vantage points in the game to create this sensation of perception being a mobile and active process) to serve as a visual inspiration for the book’s design. I was really happy to see Felipe go for the slightly retrofuturist, steampunk aesthetic in response. The other books he had previously designed for Flugschriften already had a very strong visuality, combining text and images in a playful and creative way. So it was only natural that for a book on perception, on how we see the world, he would adopt a style that would challenge the reader visually, that would often perhaps make them squint or that would even strain their eyes. It’s because reading is of course also a form of seeing. I wanted the book to convey that – and to blur the line between letters and images to some extent.

As we are a video game website, we have to ask : ) For you, are video games an art form?

The first thing I would like to say is that video games are massively interesting – although presumably I don’t need to say this to the readers of a video games website! I am also aware that games are interesting on their own terms and that they should be encountered on those terms. I can see it being really annoying for the gaming community when you get academics, artists and curators who know very little about games suddenly proselytising about games’ cultural value, but only recognising this value in conventionally recognisable terms, i.e. seeing video games as literature or as art. There is of course a strong creative, artistic dimension to video games and many video games have been – and should be – shown in art galleries as places where particular audiences come to consume culture. So in this sense, yes, video games are an art form. But I think they’re also much more than this.

You can download for free Joanna Zylinska’s book here.

Leave a Comment