Madelon Hoedt, author of the Narrative Design and Authorship in Bloodborne: An Analysis of the Horror Videogame.

Madelon, hi! We are thrilled to be able to talk to you about your book on Bloodborne! Gaming studies have different approaches and analyses concerning video games, so, how would you briefly explain your book. What is it exactly about, what is so intriguing about the notion of authorship that you decided that it must be in the title?

Why Bloodborne?

I have been gaming for a while, but at the same time came to it quite late, at 18, 19 years old. As a result, I didn’t really regard myself as a skilled gamer, so when Dark Souls came out, including reports of its difficulty, I very quickly dismissed it as “not for me”. Bloodborne was the same, initially, but the world presented within it combines everything I like: a dark, warped cityscape; original monstrosities; escalating terror… I was still worried about its difficulty, but could not resist exploring Yharnam for myself, and my enthusiasm for the game is what fuelled the project. At its heart, it is a fan letter, but one coming from a particular academic viewpoint.

The reason that Bloodborne was chosen for this analysis was, firstly, my preference for its game world, but also because I feel it is the best example out of the Soulsborne series of Miyazaki’s design ethos. In Bloodborne, in particular, not a moment of the game is wasted; every single aspect connects to another to create an intricate web where each element of the world, whether a cut scene, an item and its description or the areas and the routes between them, has meaning and helps players to understand Yharnam and its history.

This is where the focus on authorship comes from: in recent years, Miyazaki has been called an auteur, alongside creators such as Hideo Kojima and Yoko Taro. This cannot be denied: it is clear from interviews that Miyazaki is involved in every single aspect of his games, from aesthetics to map design to the lyrics of the soundtrack. Yet once the game is done, this ownership is handed over to the players. Amidst the many detailed discussions of the lore of all Soulsborne games, Miyazaki is unlikely to add his voice and his interpretation, instead of leaving it entirely up to the players as to what story they construct. Undoubtedly an auteur in his approach to design, Miyazaki fails to fulfil this role truly. The book, then, starts from this realization: it presents a reading of Bloodborne’s lore, world and mechanics, and analyzes how each of these is constructed to aid players in their reading of the narrative.

You are a Senior Lecturer in Drama at the Department of drama, theatre, and performance at the University of Huddersfield. How does this study coincide with your previous work? How is drama connected to video games? I presume some people who are not part of academia (or maybe people within it) would wonder how you have such diverse research interests.

I have worked in academia for ten years, and during that time, I have alternated between lecturing in drama and in game studies. Across these, there are two key elements that unite my research: a focus on Gothic and horror studies, and an interest in interactive and immersive experiences. My work in drama focuses on popular forms of immersive theatre, such as scare attractions and pervasive games, and from the start I have looked to research from the field of game studies as a way to approach these more interactive forms. For me, and with the niche that I’m working in (as opposed to more classic and traditional forms of theatre), I see the two as an extension of one another, with a variety of experiences delivered along a spectrum of immersion, interactivity and performativity.

How do you see the state of video game studies, or gaming studies, today?

Game studies is an interesting field in that it is constantly working to push its own boundaries. Working in a discipline that is continuously growing and expanding, as well as developing in new directions due to advancement of the hardware involved in it, the opportunities for research are rich. There are a number of amazing scholars doing incredibly interesting work, on individual games, game genres, aspects of design and on players and communities. At the same time, there is a constant struggle, if you will, to keep abreast of these developments, and for the scholarship to remain up-to-date. Most importantly, though, I feel it is a fascinating field with a lot of room for early career researchers to help bridge the gaps in knowledge and theory that currently exist.

In your opinion, why are games like Dark Souls, Demon’s Souls, Bloodborne so popular today? We see some other games today that try to follow this kind of formula of high difficulty, slow combat, dark and gritty atmosphere, like Sekiro, for example. Does it have something to do with nostalgia? Yearning for the ‘’good old’ days’’ when a lot more titles were harder than they are today?

I would argue that the lure of the Soulsborne and, by extension, the Souls-like games is not so much to do with nostalgia as it is with freedom. I think that what these titles have brought back is a sense of and room for exploration and the difficulty, in my opinion, is only a subset of this. The lack of handholding within this subgenre has often been mentioned, and for me, the draw of these games has been the sense of and reward for exploration, of discovering new hidden areas or unlocking a shortcut. In some ways, Soulsborne is almost a puzzle, with each difficult enemy and boss simply a challenge to be figured out, with a certain degree of freedom in the choice of playstyle. Players are given a large number of options in terms of different weapon types or strategies as to how they wish to meet these challenges. I would argue that it is this element of choice in how to play that sets these games apart from different experiences, where tutorials and mission-based gameplay can be more restrictive.

How important is it to think about the games as something more than mere fun and/or relaxation?

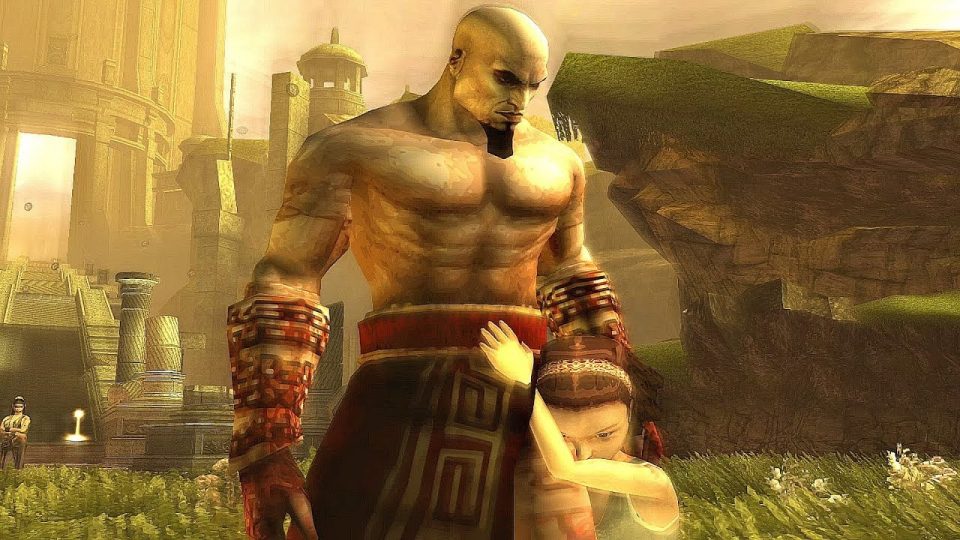

It has been said before, but the interactive nature of games allows them to put players in a specific position in relation to the material. All of a sudden, despite the action playing out on a screen, you are forced to do something, to push a button in order to perform an action. There have been a lot of jokes about this (such as the now notorious “press X to Jason” in Heavy Rain), yet when implemented correctly, it can be incredibly powerful. One of the first game franchises I played a lot of was God of War, and initially, I only had access to the PSP titles. In GoW: Chains of Olympus, just before the final boss fight, Kratos is reunited with his daughter Calliope, slain by his own hand. Yet the reunion is not a sweet one, and Kratos is forced to choose between remaining with Penelope or saving the world, and the both of them, from destruction. At this point, the game hands control back to the player and force them to repeatedly hit O to push Calliope away so Kratos can move on, but she clings on, and the player is asked to do the same again. Hidden amidst the spectacle and overt violence that the God of War games are famed for, it was a sudden moment of tenderness, made all the more impactful by the fact that I, the player, was forced to perform this action, knowing Kratos’ story, and what this renewed separation from his daughter would mean to him. This is certainly not the best example of this strategy, but it was the first one I encountered and goes some way to show the potential impact of allowing players to interact with this type of material. It is a strategy which is employed in numerous triple-A titles and has become the core gameplay in indie titles such as This War of Mine and Hellblade: Senua’s Sacrifice, where players are confronted with serious themes and (moral) choices.

At the same time, I feel that it does games a disservice to not consider them as fun and relaxation. Some games are just silly, and they are meant to be, or they can offer a sense of humor while dealing with the more serious subject matter. It all comes down to the intention of the designers, and the experience they wish to create for their players.

I presume you use some of the video game lore in your classes as an example or as case studies to explain something in more detail or to make everything more interesting. How do students react to this kind of approach?

I primarily use a selection of videogames as case studies, and as a means of exploring certain concepts in more detail. The particular elements of analysis that I teach, in the realms of semiotics and representation, can be quite vague, and the use of examples can help make the material more grounded for students and easier to grasp. It also allows for lively classroom discussion as students bring in their own examples, and for me to find out more about games I may not have played; I tend to favour singleplayer over multiplayer games, but learned a lot from my students when the battle royale craze first hit! For me, the classroom is very much a two-way street, where I offer information, but I expect my students to consider and apply these concepts in new ways, and I love hearing about their own analyses of the experiences they have encountered.

Are there any other books that you would like to recommend to our readers? Something that would arise interest within fans, gamers, and scholars alike?

One of my go-to books will always be Rules of Play by Katie Salen and Eric Zimmerman. Although it is getting a bit old now (it was published in the early 2000s), it remains an excellent starting point on a lot of topics related to game studies and offers lists of recommended reading to explore more.

In terms of my research, and where I am currently heading, I have found Mark JP Wolf’s book Building Imaginary Worlds very helpful. It is more focused on literary and cinematic texts, but Wolf offers an interesting way to approach the examination of worldbuilding that I have used in my analysis of Bloodborne and other work. Finally, there is an increasing interest in writing on individual games, with books out on Doom, Myst and Silent Hill, so it is always worth seeing what might have been published on games you like.

How can we get your book?

The easiest way is via Amazon, or directly from the publisher; it is available in paperback and ebook format.

https://www.amazon.com/Narrative-Design-Authorship-Bloodborne-Videogame/dp/1476672180

https://mcfarlandbooks.com/product/narrative-design-and-authorship-in-bloodborne/

So, games in 2019. As someone who likes games and plays them, what are your favorites of the year?

I have to admit that I’m always a little bit behind, so alongside recent releases, I try to dig into my backlog. From the older games list, Hollow Knight has definitely been a highlight this year as one of the best metroidvanias since Castlevania: Symphony of the Knight, with a lovely aesthetic and sharp, interesting mechanics. Staying with that theme, my game of 2019 released this year is, without a doubt, Bloodstained: Ritual of the Night. As implied by the inclusion here of Hollow Knight, I have a huge love for Metroidvanias, specifically Castlevania, and I had a whale of a time with Bloodstained. It delivers exactly what I wanted from a new Igarashi title, with excellent gameplay and tight controls. It also handles its heritage with integrity in its design, keeping the hallmarks of the better titles from the Castlevania franchise, as well as having some fun with it, with throwbacks to previous games (such as the choice of a certain voice actor, and the inclusion of the Might’ve Known trophy, for breaking a secret wall).

How do you evaluate the indie games scene within all this? Have indie games managed to provide some new experiences, stories, narratives that were not so presented in the industry? Could you recommend some games who did the most exciting work in that manner?

The most exciting aspect of the indie scene, for me, is the potential for more diverse voices and approaches. I’m a sucker for quirky game design, even if the game itself isn’t wholly successful. For example, I was quickly sold on Darkest Dungeon as soon as I found out about the stress mechanic; on the storybook aesthetic of Child of Light; on the use of the narrator in Bastion; or playing as a small child in Among the Sleep. I’m also a sucker for a good story, and as a result, have really enjoyed titles like The Vanishing of Ethan Carter and Oxenfree, as well as the more abstract approach to the narrative from games like Limbo and Virginia.

In addition, it seems that the smaller scale of both design and team of indie titles can lend a certain focus to an experience that can make it sharper and more poignant than a sprawling open-world game. The vision of the two-man team behind Salt and Sanctuary is a great example of this. This focus often extends to the way in which indie developers approach their designs, making games such as Valiant Hearts, Never Alone, Beyond Eyes and Papo and Yo. Each of these titles allows access to a particular type of knowledge and experience, to someone’s story, that I otherwise would not have had.

I’ve also found that, as I get older, and work gets more stressful, I don’t always have time to play the huge games that take anywhere from 40 to 100+ hours to complete. For this reason, having a small indie title that takes maybe 4 to 6 hours to finish has been something I have gravitated towards more and more in recent years.

What are your plans now? Are you planning to work on video games in the future? Do you plan to do more studies about some other games?

The aim is definitely to continue to find a middle ground between my writing on performance and on games, if only for my own enjoyment. I’ve got two book chapters that are out, or about to be released, about the use of the zombie motif in Siren: Blood Curse and the inversion of the city in the Metro games, and I expect to keep doing such short explorations in the future. It is unlikely that I’ll do another full-length study on a particular game or franchise. I’m currently working on a manuscript on horror in performance, I know I’ll be taking a break from big book projects for a while after completing that, but never say never…

Leave a Comment